Deep in the Niyamgiri Hills in Orissa, the Dongria Kondh tribe have been fighting a decade-long battle against London-based mining company, Vedanta, who have turned these jungles into a battleground. The Dongria Kondh worship the Niyam Dongar hill under which lies two billion dollars worth of bauxite.

Enter a caption

On August 13, two days before India celebrated its 67th Independence Day, a tiny village deep inside the forests of Orissa tasted the fruits of freedom.

Khambesi, the village of 105 Dongria Kondh tribals, isn’t easily accessible. The beautiful hamlet in Rayagada district isn’t connected by road or rail networks. It can be reached only by walking nine km through thick forest and after crossing four streams and a river. But on that day, several government officials, social workers, research scholars, and journalists headed for Khambesi to witness the proceedings of a gram sabha, or a meeting of the village council.

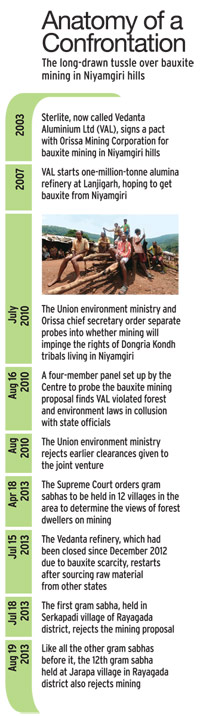

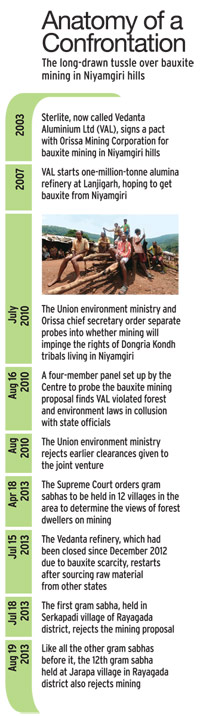

The meeting was to decide whether a joint venture of state-run Orissa Mining Corporation (OMC) and Vedanta Aluminium Ltd, a unit of billionaire Anil Agarwal’s London-listed mining giant Vedanta Resources Plc, should be allowed to extract bauxite from Niyamgiri hills. The hill range is spread over 250 sq km and contains bauxite reserves of about 70 million tonnes. As the meeting began, villagers came forward one after another to voice their opinions on the mining project. They spoke about how the project threatens their religious rights and how it would destroy the pristine forests as well as their livelihoods.

“We have lived here for so long. How can the government sell our donger (forest) now,” Lashkiya Sikata, a middle-aged woman, told the meeting held under heavy security cover of state police and central paramilitary forces. Another villager, Rikota Bhali, said the forest was the abode of their lord – Niyam Raja – and that their culture would vanish if the forest was taken away from them. Some women grew agitated. Kutruka Kunjhi took the mike from the presiding official and roared, “No one has the rights to our forest – neither the government nor the company. We will shoot down with our arrows those who force us to give up our forest.”

Soon after, the villagers voted unanimously to oppose mining in their revered Niyamgiri hills.

Khambesi is one of a dozen villages inhabited by Dongria Kondh and Kutia Kondh tribes in Rayagada and Kalahandi districts where the gram sabhas were held. These gram sabhas were organised by the Orissa government between July 18 and August 19. All of them rejected mining on similar grounds. While 112 villages fall in the Niyamgiri hill range, the state government selected 12 villages in a 1.5 km radius for the gram sabhas as only these fall in the mining zone, says Bijay Ketan Upadhyaya, District Collector of Kalahandi.

The genesis of the landmark referendums lies in a directive of the Union Ministry of Environment and Forests in August 2010 rejecting forest clearance to the bauxite mining project. OMC later challenged the ministry’s denial in the Supreme Court. In April, the Supreme Court ordered the state government to organise gram sabhas under the Forest Rights Act of 2006 to determine the views of forest dwellers on whether mining should be allowed or not.

The gram sabhas’ unanimous verdict is not the last word, but it will certainly influence the central government’s final decision on granting forest clearance for the mining lease. Certainly, the outcome is a jolt to Vedanta. The company has invested Rs5,000 crore to set up an alumina refinery with a capacity of one million tonnes a year at Lanjigarh in Kalahandi. The refinery was to get bauxite, the main aluminium ore, from Niyamgiri and was sourcing the raw material from other states in the interim. In fact, the company shut down the refinery due to bauxite scarcity in December last year and resumed partial production only in July. Mining from Niyamgiri is also vital for the company’s plans to expand the refinery to five million tonnes.

The company is unfazed, however. In its 2013 annual report, released after the Supreme Court verdict, Vedanta Resources said it expected to receive mining approval by September and planned to start bauxite production in two years’ time. The company also expected approvals for refinery expansion by January 2014, according to the report. But, it had added that the timelines were not in its control. A spokesman for Vedanta Aluminium told Business Today it was the state government’s responsibility to give bauxite to the company. The state government had promised the company 150 million tonnes of bauxite and it must help Vedanta source the raw material locally for the Lanjigarh refinery, he said.

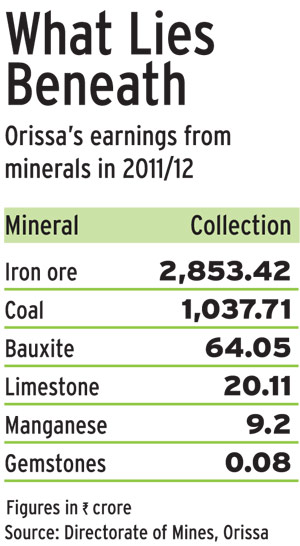

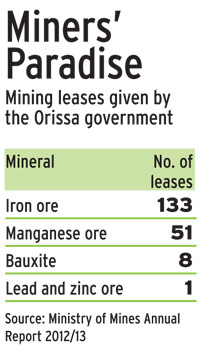

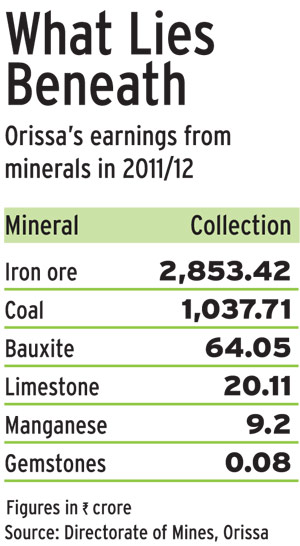

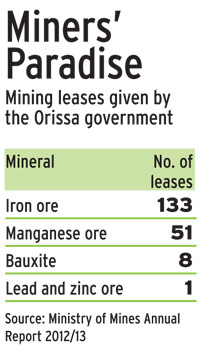

Orissa is one of the most mineral-rich states in the country. It has more than half of India’s bauxite reserves and is the largest producer of aluminium in the country. It has 90 per cent of India’s chromite and more than a third of ironore reserves. Not surprisingly, the state earns massive revenue from minerals. Its non-tax revenue from mines surged to Rs5,695 crore in 2012/13 from Rs3,300 crore two years before.

Like its mineral-rich neighbours Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh, Orissa is also encouraging steel, aluminium and power companies to set up factories, promising them mines to extract iron ore, bauxi te and coal. And like its neighbours, Orissa also is witnessing people’s resistance to these projects. Besides Vedanta, a number of companies including South Korean steel maker Posco are facing problems in getting mining leases, environment and forest clearances, and in acquiring land. On July 17, a day before the gram sabhas began, global steel giant ArcelorMittal scrapped its Rs50,000 crore project in Orissa. The company said it had been unable to acquire land and iron-ore mining blocks for the 12-million-tonn

te and coal. And like its neighbours, Orissa also is witnessing people’s resistance to these projects. Besides Vedanta, a number of companies including South Korean steel maker Posco are facing problems in getting mining leases, environment and forest clearances, and in acquiring land. On July 17, a day before the gram sabhas began, global steel giant ArcelorMittal scrapped its Rs50,000 crore project in Orissa. The company said it had been unable to acquire land and iron-ore mining blocks for the 12-million-tonn

e project more than six years after signing an initial pact with the state government in December 2006.

Critics say the state government signed pacts with various companies promising them thousands of acres of land without taking into account the concerns of locals. Bijaya Kumar Babu, a local social activist, says tribals across India are struggling to establish their rights over their own land. “For a long time they were being treated as secondclass citizens,” adds Manish Kumar, a research associate from National Law University, Delhi, who was present at the Khambesi gram sabha.

Rana Roy, a research scholar in forestry from Canada’s University of Toronto who also observed the proceedings of the gram sabha, says the Forest Rights Act, if implemented properly, can act as a shield for the tribals in the long term. But he adds that government officials and civil society groups have not done much to make the tribals adequately aware of the law. “The tribals see the Act as something that will limit their rights, which is not the case,” says Roy, who is studying the implementation of the law in Kandhamal and Deogarh districts of Orissa.

Biswajit Mohanty, a board member at anti-graft group Transparency International India,  says Orissa’s mining sector is seeing a little bit of accountability for the first time. “Mining laws were not being enforced,” says Mohanty, who filed the first court case against Vedanta’s projects in Lanjigarh and Niyamgiri almost a decade ago. “It was a free-for-all for miners who did business by bribing officers and politicians.”

says Orissa’s mining sector is seeing a little bit of accountability for the first time. “Mining laws were not being enforced,” says Mohanty, who filed the first court case against Vedanta’s projects in Lanjigarh and Niyamgiri almost a decade ago. “It was a free-for-all for miners who did business by bribing officers and politicians.”

Bhalachandra Sarangi, a local activist of the Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist), says the gram sabhas have established the forest dwellers’ individual, community and cultural rights. The tribals, he says, would have agreed to a project such as a fruit processing unit that would help them earn some more money from the forest produce they sell. “But what will they get from mining?”

State government officials, however, defend industrial and mining projects. Umesh Chandra Jena, Deputy Director of Mines at Orissa’s Directorate of Mines, says mining is responsible for only three per cent forest loss while road construction, irrigation and transmission projects take away much more, he says. Moreover, trees can be planted again on mined land. “Tata Steel’s iron-ore mine at Noamundi and National Aluminium Company’s Damanjodi project are prime examples of vegetation post mining,” he adds. Upadhyaya, the Kalahandi collector, says the issue has been heavily politicised and has harmed the state’s investment climate. He feels that Maoists are also exploiting the discontent among tribals to strengthen their presence in the area. “Wherever there are mineral deposits locals will say they worship acco rding to their tradition, but it is the state government which should take the final call,” he says, adding that locals will benefit from industrial and mining projects. Some social scientists seem to agree. “The l

rding to their tradition, but it is the state government which should take the final call,” he says, adding that locals will benefit from industrial and mining projects. Some social scientists seem to agree. “The l

ong battle over Niyamgiri throws up some knotty problems,” Barcelonabased researchers Leah Temper and Joan Martinez-Alier wrote on the website of Environmental Justice Organisations, Liabilities and Trade, a project that supports academics and environmental groups. “For one, exactly how much of a veto can local communities have?” asked the two researchers of Autonomous University of Barcelona. “This is not a question of property rights, since the minerals underground are owned by the state, and the land above ground is not owned by the villages.”

So, what does the verdict of gram sabhas mean for the mining industry? Has this set a precedent that could fuel demands for similar people’s courts to decide on industrial projects? They certainly can. But, say Temper and Martinez-Alier, it is unlikely that this will lead to allowing any community a veto on religious grounds over the use of land for industrial projects.

te and coal. And like its neighbours, Orissa also is witnessing people’s resistance to these projects. Besides Vedanta, a number of companies including South Korean steel maker Posco are facing problems in getting mining leases, environment and forest clearances, and in acquiring land. On July 17, a day before the gram sabhas began, global steel giant ArcelorMittal scrapped its Rs50,000 crore project in Orissa. The company said it had been unable to acquire land and iron-ore mining blocks for the 12-million-tonn

te and coal. And like its neighbours, Orissa also is witnessing people’s resistance to these projects. Besides Vedanta, a number of companies including South Korean steel maker Posco are facing problems in getting mining leases, environment and forest clearances, and in acquiring land. On July 17, a day before the gram sabhas began, global steel giant ArcelorMittal scrapped its Rs50,000 crore project in Orissa. The company said it had been unable to acquire land and iron-ore mining blocks for the 12-million-tonn

says Orissa’s mining sector is seeing a little bit of accountability for the first time. “Mining laws were not being enforced,” says Mohanty, who filed the first court case against Vedanta’s projects in Lanjigarh and Niyamgiri almost a decade ago. “It was a free-for-all for miners who did business by bribing officers and politicians.”

says Orissa’s mining sector is seeing a little bit of accountability for the first time. “Mining laws were not being enforced,” says Mohanty, who filed the first court case against Vedanta’s projects in Lanjigarh and Niyamgiri almost a decade ago. “It was a free-for-all for miners who did business by bribing officers and politicians.” rding to their tradition, but it is the state government which should take the final call,” he says, adding that locals will benefit from industrial and mining projects. Some social scientists seem to agree. “The l

rding to their tradition, but it is the state government which should take the final call,” he says, adding that locals will benefit from industrial and mining projects. Some social scientists seem to agree. “The l