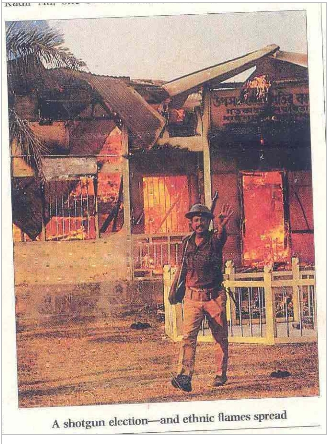

It was February 1983. For more than three years the state had been caught in a vortex of agitations, bandhs, killings and curfews. The central government led by Indira Gandhi had declared assembly elections and parliamentary election to be held simultaneously in February. The Assamese nationalist organisations, AASU (All Assam Students’ Union) and AAGSP (All Assam Gana Sangram Parishad), which were spearheading the Assam Movement [1] (1979-1985) had called for a boycott of the elections. The electoral rolls contained many illegal immigrants they alleged. Already in 1979 Assam had become the first state of independent India to have missed the national parliamentary elections on the same issue. Some political parties, as well as Bodo and Bengali groups, welcomed the 1983 elections. Clashes had started to break out well before February. In February 1983 things were on the boil.

Nellie is a small town about 50 kilometres east of Guwahati. On 18th of February Bengali Muslims living in 14 adjoining villages near the town were attacked and butchered in a pre-planned manner. The immediate provocation was a rumour that children belonging to the local tribes had been killed by the Muslims. The real reason could be more political. There were reports that the Muslims of the area had taken part in the elections in large numbers, which were held on 14th of February. It’s also suspected that Hindu rightist cadre of the Rashtriya Swayangsevak Sangh who had infiltrated the AASU may have played a part [2].

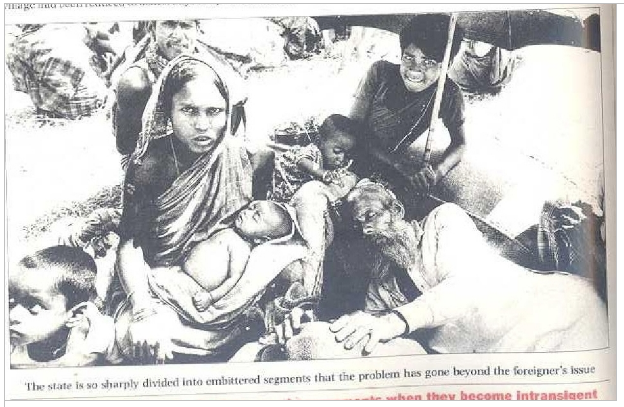

But complicity of other elements cannot be ruled out. Three days before the massacre a local police station had sent out a warning “one thousand Assamese villagers [are] getting ready to attack…with deadly weapons”. This was ignored. The attackers were mainly of the Lalung tribe, who were accompanied by some Assamese. According to the official estimates 1,819 men, women and children were killed, unofficially the number crosses three thousand. Primitive weapons such as swords, spears, machetes, guns, sticks were used. A large proportion of those killed were women and children: as if the killers wanted to snuff out the future generation of illegal foreigners.

Till date, no one has been convicted. The police had filed charge sheets, which were dropped later on. The Tiwari Inquiry Commission, constituted in 1983, submitted its report in 1984. The report has not been made public by any of the successive state governments. The secrecy has lived to this day. In 2004 the government prevented a Japanese scholar from delivering a talk on the massacre at Omeo Kumar Das Institute, Guwahati.

After this brief description let us return to February, 1983. Besides Nellie other alarming incidents were being heard. A local Congress leader who was a family friend, was hacked to death. One night some college students of the town went on a raid of a Muslim settlement located at the outskirt; in the clash a student leader got lynched. Houses and shops were being set on fire. There was a popular slogan at that time, Ei zui zawlise! Zawlibo, zawlise! The fire is raging, it will keep on burning. Holding aloft burning torches, agitators would take out night processions through the town. They usually consisted of a large number of school and college students. To add to the excitement BSF jawans were camping at schools, which meant an indefinite suspension of classes. Sadly, the parents did not have the stomach for so much adrenaline rush. Locking the house they went for a long trip out of Assam until things could calm down. By the time the Assam Movement wound up in 1985 with the signing of Assam Accord between Rajiv Gandhi and the leaders of the Movement some 4000 people had been killed.

Thus, Nellie has been with us. Nellie, the place, is a regular mufassil – deep green paddy fields, dark hills of Meghalaya at a distance, clumps of teaks and bushes, a busy market place, a Durga Puja community hall, and going by the clothes a high percentage of Muslims. No landmark could be seen to indicate what went on on that day of 1983.

But this was expected. Unlike Delhi 1984 or Gujarat 2002, where the State had to show the minimum gestures of justice because sometimes the ghosts come back to haunt, Nellie is off the radar of state politics, let alone national politics. Who remembers a carnage where the poor rural Muslims perished. That the victims were massacred during the heat of a movement against illegal immigrants further robs them of their share of justice. The dead of Delhi and Gujarat may not have had the right religion. There is scarcely any doubt however that they were Indian citizens and not trespassers. Moreover, that it took place at a border outpost, far away from the Indian heartland, thickens the national amnesia. Nellie therefore is not heard of. Not even when one massacre is deployed as an indirect justification for a subsequent massacre, for Nellie possesses no utilitarian value as a basis for further massacres. To the national collective memory Nellie has not happened.

The only people whom the ghosts of Nellie are troubling seem to be those of the Left. Since the Assam Movement, an important episode of which Nellie was, Left politics in the state has waned. In the 1978 state Assembly elections the CPI had won 4.3% of the popular votes (5 seats in a house of 126), CPI(M) received 5.6% of the votes (11 seats). These numbers were a marked improvement over their previous performance. The Left was on the rise. The Movement began in 1979. In the latest 2011 assembly elections CPI and CPI(M) have won 0.52% and 1.13% of popular votes respectively. As for the non-traditional Left, it has been reported that the Maoists have been developing their base in Assam, specially among the Tea Tribe community. There is lack of substantive proof for the claim. The recent encounter killing of four Maoist cadre has been cited by the chief minister as evidence. But questions have been raised if it was a genuine encounter, or if the young men were at all Maoists.

Along with the alleged bahiragatas (those who have come from outside) what else was massacred in Nellie? Why have the Left not been able to recapture the popular support, admittedly limited, that it once enjoyed? If this question is not clinched it is doubtful if a coherent and vibrant Left politics would gain ground in Assam.

What makes incidents of such nature difficult to come to grips with and take a position on is the intermingling of different cross-currents. Many have commented that on the question of nationality struggles the response of the traditional Left has lacked clarity. It would be useful to examine the reasons why this has been so. Let us briefly probe some of the complexities involved.

First, those who were killed in Nellie were mostly of peasant, agricultural labourer background. In general, there can be little doubt that for most of the bahiragata victims of the Andolan the main source of income was their labour, mostly unskilled. From the first principle of Left politics a support for their lives and livelihood follows.

Secondly, it is possible that many of them were immigrants from Bangladesh or East Pakistan [3]. In the documents of the Left parties territorial integrity of the nation State and sanctity of its boundaries are given cardinal importance [4]. From the point of view of Left politics the simple agenda of upholding the rights of the working people gets entangled with their legitimacy as citizen.

Thirdly, those on the side of the Movement were in it in the name of protecting their national interest. It can be reasonably argued that the nationalities in the region are often at the receiving end of economic exploitation, resource extraction and State oppression. Protecting the rights of immigrant labourers gets fraught with political confusion as the labourers could be on the wrong side of nationality struggles, which the Left espouses. Many a time the immigrants and the indigenous communities are locked in a battle over same resources. This renders a resolution almost impossible.

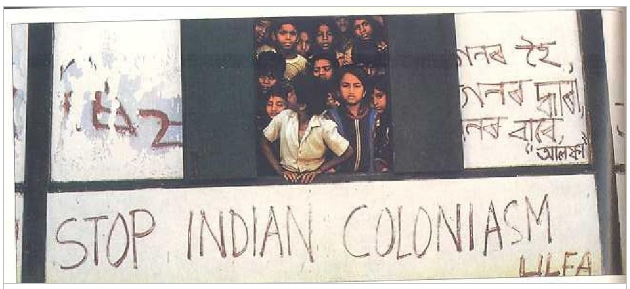

Fourthly, nationality struggles often assume a secessionist edge. In this narrative, to the metropolis Indian state the Northeast is a colony. The colony is held because it benefits the metropolis economically and militarily, among other things. Only a territorial separation can enable the local communities to embark on a journey of national rejuvenation and development. The traditional Left parties however hold the boundaries of the Indian nation state supreme, as has been pointed out above. Demand for right of self-determination is alright, but it has to be accommodated within the constitutional perimeter. From the point of view of the nationality movement this makes the Left suspect, if its pro-labour ideology was not bad enough. Many Left supporters had to face the accusation of being stooges of the Indian establishment during the Assam Movement. One reason was that Left parties decided to participate in the 1983 elections. But their inability, or reluctance, to imagine nationality movements which do not conform to national boundaries may be an inner, contributory factor.

Before we conclude two disclaimers are in order. First, this short note does not claim, nor did it intend, to cut through the complex web of political currents in the Northeast. It tries to understand some of the complexities involved. These include, to name a few, cross-border labour flows, nationality struggles [5], the nation State’s power dynamics of self-preservation, attendant ebbs and flows of capital, dimensions of religion, ethnicity and language. It appears prima facie that the traditional Left understanding of nationality struggles through the prism of paramount-ness of the nation State is a handicap. By according the borders a position of sacrosanctity the Left alienates itself from the either quarter of nationality struggles and immigrant labourers.

Secondly, immigration is not as major an issue in some other states of the Northeast as it is in Assam. In Assam the decadal population growth has been falling of late. At present it is less than the all-India population growth rate. This perhaps indicates that immigration has been on the decline [6]. Having noted this, it is also recognised that the state politics has been through a watershed during the early 1980s, from which the Left has not recovered. The fertile socio-political space which could question the exploiting nature of the Indian State, or its capital, has been occupied by identity politics of different hues, much to the benefit of the State. On the thirtieth anniversary of Nellie genocide a fresh and honest attempt to understand the contemporary society of Assam could be the Left’s homage to the hundreds of peasants and farm labourers whose corpse its political narrative is yet to embrace.

(Acknowledgement: scanned images from an old issue of India Today have been used. I also thank Ashok Prasad for raising some simple and penetrating questions.)

Further Readings:

Anju Azad and Diganta Sharma (2009) “Nellie 1983” TwoCirclesNet, February 18, http://twocircles.net/special_reports/nellie_1983.html

Sanjib Baruah (1986) “Immigration, Ethnic Conflict, and Political Turmoil – Assam, 1979-1985,” Asian Survey, Vol. 26, No. 11 (November, 1986), pp. 1184-1206.

Teresa Rehman (2006) “The Horror’s Nagging Shadow” Tehelka, September 30 http://www.tehelka.com/story_main19.asp?filename=Ne093006the_horrors.asp

Myron Weiner (1983) “The Political Demography of Assam’s Anti-Immigrant Movement,” Population and Development Review, Vol. 9, No. 2 (June, 1983), pp. 279-292.

Notes

1. The English phrase which is often used to refer to the churning which went on in those years is ‘Assam Agitation’. I am using the phrase ‘Assam Movement’, a more correct translation of Axom Andolan, the phrase which is used in Assamese.

2. http://twocircles.net/2009feb20/who_responsible_nellie_massacre.html

3. A main demand of the Assam Movement was to use 1961 as the cut-off year to determine which migrants would be considered illegal and are to be deported. Those who immigrated between 1961 and 1971 were from East Pakistan.

4. For instance, CPI(M) party programme reads:

5.4 The problems of national unity have been aggravated due to the bourgeois-landlord policies pursued after independence. The north eastern region of the country which is home to a large number of minority nationalities and ethnic groups has suffered the most from the uneven development and regional imbalances fostered by capitalist development. This has provided fertile ground for the growth of extremist elements who advocate separatism and are utilised by imperialist agencies. The violent activities of the extremists and the ethnic strife hamper developmental work and democratic activities.

5. Confounding any neat theorisation further, nationality struggles are at times fought against one another. During the Assam Movement numerous clashes broke out between different indigenous groups, specially between the Bodo and Assamese orgnisations.

6. An argument of the proponents of the Assam Movement rested on the high population growth of Assam compared to the national average. This was put forward as an evidence of immigration.

By: Debashis

General Secretary, Rationalists’ and Humanists’ Forum of India