In 2012, I was a guest speaker on ‘Rationalism in India’ in ‘Think Fest’ where I met this 84 years young man who looked almost like Charles Darwin.

He was none other than James “The Amazing Randi” who passed away on Oct 20, 2020 at 92.

I had knew him since I was a kid. To my surprise he said that he had read

my articles too. (We both wrote for same skeptic magazines)

In no time, we, two young men became good friends, “Call me ‘Randi’ my buddy” he told me with a Darwinian grin😊

In February 2006, Randi underwent coronary artery bypass surgery. Soon after that, Randi was diagnosed with colorectal cancer in June 2009. He had a series of tumors removed from his intestines. His body was bend to merely 4ft because of chemotherapy.

But that could not stop him. He was still travelling the whole world with his mission.

Randi was a leading magician and one of the greatest escape artists in history, famously escaping a straight-jacket while being suspended upside down in a helicopter over Niagara Falls. The Amazing Randi devoted the second part of his life, an entire career in its own right, to debunking mysticism and those who profit off of ignorance. He practiced the art of magic openly and with pride, and never shrouded his own miracles under a false guise of the supernatural. He famously debunked the claimed psychic Uri Geller, faith healers, and all who took advantage of the gullible for their own financial gain.

In his essay “Why I Deny Religion, How Silly and Fantastic It Is, and Why I’m a Dedicated and Vociferous Bright”, Randi, who identifies himself as an atheist, opined that many accounts in religious texts, including the virgin birth, the miracles of Jesus Christ, and the parting of the Red Sea by Moses, are not believable. Randi refers to the Virgin Mary as being “impregnated by a ghost of some sort, and as a result produced a son who could walk on water, raise the dead, turn water into wine, and multiply loaves of bread and fishes” and questions how Adam and Eve “could have two sons, one of whom killed the other, and yet managed to populate the Earth without committing incest”. He wrote that, compared to the Bible, “The Wizard of Oz is more believable. And much more fun.”

Clarifying his view of atheism, Randi wrote “I’ve said it before: there are two sorts of atheists. One sort claims that there is no deity, the other claims that there is no evidence that proves the existence of a deity; I belong to the latter group, because if I were to claim that no god exists, I would have to produce evidence to establish that claim, and I cannot. Religious persons have by far the easier position; they say they believe in a deity because that’s their preference, and they’ve read it in a book. That’s their right.

Debashis Rationalist (aka Magician Dave) with Amazing Randi

In An Encyclopedia of Claims, Frauds, and Hoaxes of the Occult and Supernatural (1995), he examines various spiritual practices skeptically. Of the meditation techniques of Guru Maharaj Ji, he writes “Only the very naive were convinced that they had been let in on some sort of celestial secret.” In 2003, he was one of the signers of the Humanist Manifesto.

In a discussion with Kendrick Frazier at CSICon 2016, Randi stated “I think that a belief in a deity is … an unprovable claim … and a rather ridiculous claim. It is an easy way out to explain things to which we have no answer.” He then summarized his current concern with religious belief as follows:

A belief in a god is one of the most damaging things that infests humanity at this particular moment in history.

Amazing Randi, Debashis Rationalist (aka Magician Dave) and DJ Gothe

Randi often said “One day, I’m gonna die. That’s all there is to it. Hey, it’s too bad, but I’ve got to make room. I’m using a lot of oxygen and such—I think it’s good use of oxygen myself, but of course, I’m a little prejudiced on the matter.”

My heart is broken! A truly great man has left us. My dear friend, mentor.

Thank you, Randi, for helping us to protect ourselves from the very human desire to believe in the unbelievable.

We’ll miss you Randi. Be ‘Amazing’, forever in our Hearts.

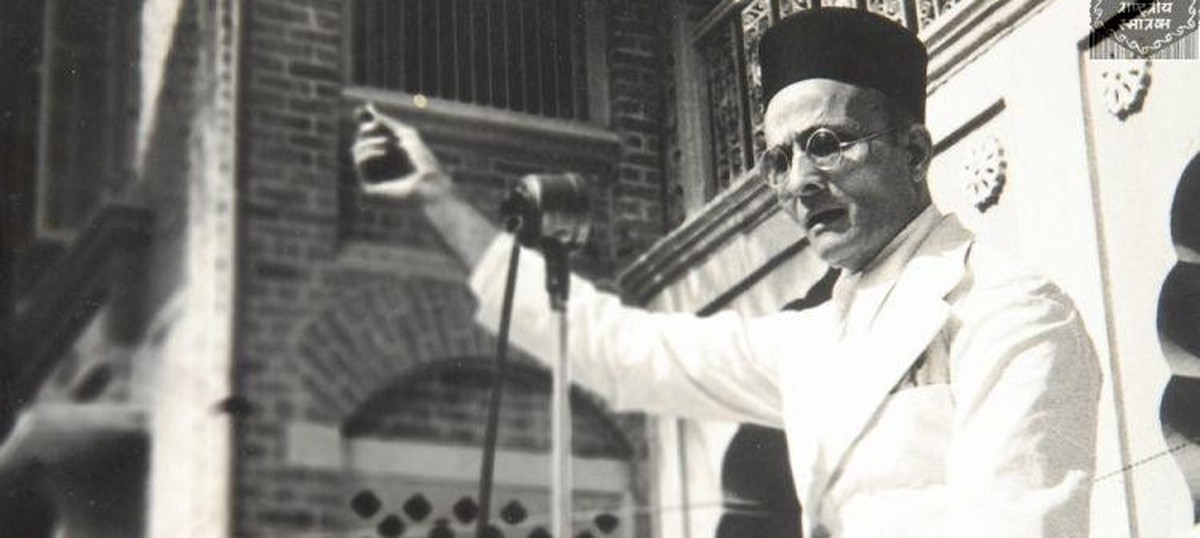

Vinayak Damodar Savarkar was declared by Prime Minister Narendra Modi to be “the true son of Mother India and inspiration for many people”, in his Twitter salutation to Savarkar on his birth anniversary on May 28 . In 2015, commemorating Savarkar on his 132nd birth anniversary, the prime minister bowed before a portrait of the Hindutva icon in remembrance of “his indomitable spirit and invaluable contribution to India’s history”.

Finance minister Arun Jaitley was quick to follow up on the act. “Today, on birth anniversary of Veer Savarkar, let us remember & pay tribute to this great freedom fighter & social-political philosopher,” he tweeted. And somewhere in the stream of Twitter accolades from numerous BJP ministers that followed, the TV anchor Rajdeep Sardesai joined the chorus, albeit with a caveat. While he disagreed “with his ideology”, Sardesai said he honoured Savarkar’s “spirit as freedom fighter”. [1]

A freedom fighter he definitely was, for a certain period in the first decade of the previous century, long before he’d begun articulating the notion of Hindutva. Savarkar was then an atheist and a rationalist.

After joining Gray’s Inn law college in London in 1906 Vinayak took accommodation at India House. Organized by expatriate social and political activist Pandit Shyamji, India House was a thriving centre for student political activities. Savarkar soon founded the Free India Society to help organize fellow Indian students with the goal of fighting for complete independence through a revolution, declaring:

“We must stop complaining about this British officer or that officer, this law or that law. There would be no end to that. Our movement must not be limited to being against any particular law, but it must be for acquiring the authority to make laws itself. In other words, we want absolute independence.”

Before leaving for England to study law, Savarkar had been a member of a secret society, Mitra Mela, which was subsequently renamed Abhinav Bharat. Its goal was to overthrow the British through violent methods.

Savarkar’s older brother, Ganesh, alias Babarao, was an Abhinav Bharat member too. The police nabbed Ganesh Savarkar and stumbled upon a stockpile of bombs. Ganesh Savarkar was sentenced to transportation for life on June 8, 1909.

His comrades decided to retaliate. On December 29, 1909, Anant Kanhere shot dead AMT Jackson, district magistrate of Nasik, as he was watching a Marathi play, Sharada, in a theatre. Jackson had committed Ganesh Savarkar to trial, but was not the judge who had banished him to the Andamans.

From Kanhere’s accomplices, whom the police arrested, were discovered Savarkar’s letters. The Browning pistol used in the assassination was linked to Savarkar, who was accused of sending 20 such weapons to India from England. A telegraphic warrant of arrest was sent to London, and Savarkar surrendered to the police on March 13, 1910. He was brought to India.

For his role in the assassination of Jackson and for waging war against the King, Savarkar was sentenced to transportation – for two terms of 50 years each – to the Andamans. He arrived in Port Blair on July 4, 1911.

When the time came to pay the price for being a revolutionary under an oppressive colonial government, Savarkar found himself converted and transformed into “the staunchest advocate of loyalty to the English government”, to use his own words.

Savarkar does seem a leader who endorsed revolutionary action as long as he wasn’t required to pay the price.

Barely a month into the hardships in the Cellular Jail, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Savarkar submitted his first mercy petition on 30 August 1911. This petition was rejected on 3 September 1911.[2]:pg.478

The second mercy petition, which he wrote on 14 November 1913, starts with bitter complaints about other convicts from his party receiving better treatment than him:

“When I came here in 1911 June, I was along with the rest of the convicts of my party taken to the office of the Chief Commissioner. There I was classed as “D” meaning dangerous prisoner; the rest of the convicts were not classed as “D”. Then I had to pass full 6 months in solitary confinement. The other convicts had not… Although my conduct during all the time was exceptionally good still at the end of these six months I was not sent out of the jail; though the other convicts who came with me were.

…For those who are term convicts the thing is different, but Sir, I have 50 years staring me in the face! How can I pull up moral energy enough to pass them in close confinement when even those concessions which the vilest of convicts can claim to smoothen their life are denied to me?”

Then, after confessing that he was misguided into taking the revolutionary road because of the “excited and hopeless situation of India in 1906-1907”, he concluded his November 14, 1913 petition by assuring the British of his conscientious conversion. “If the government in their manifold beneficence and mercy release me,” he wrote, “I for one cannot but be the staunchest advocate of… loyalty to the English government (emphasis added)”.

“Moreover my conversion to the constitutional line would bring back all those misled young men in India and abroad who were once looking up to me as their guide. I am ready to serve the Government in any capacity they like, for as my conversion is conscientious.. The Mighty alone can afford to be merciful and therefore where else can the prodigal son return but to the paternal doors of the government?” [3]

In 1917, Savarkar submitted another mercy petition, this time for a general amnesty of all political prisoners. Savarkar was informed on 1 February 1918 that the mercy petition was placed before the British Indian Government.[2]:pg.480

In his fourth mercy petition, dated March 30, 1920, Savarkar told the British that under the threat of an invasion from the north by the “fanatic hordes of Asia” who were posing as “friends”, he was convinced that “every intelligent lover of India would heartily and loyally co-operate with the British people in the interests of India herself.”

After reassuring the colonial government that he was trying his “humble best to render the hands of the British dominion a bond of love and respect,” Savarkar went on to exalt the English empire: “Such an Empire as is foreshadowed in the Proclamation, wins my hearty adherence”. “But”, he added:

“if the Government wants a further security from me then I and my brother are perfectly willing to give a pledge of not participating in politics for a definite and reasonable period that the Government would indicate… This or any pledge, e.g., of remaining in a particular province or reporting our movements to the police for a definite period after our release – any such reasonable conditions meant genuinely to ensure the safety of the State would be gladly accepted by me and my brother.” [2]:pg.472-476 , [4]

In 1920, the Indian National Congress and leaders such as Mahatma Gandhi, Vithalbhai Patel and Bal Gangadhar Tilak demanded his unconditional release. Savarkar signed a statement endorsing his trial, verdict and British law, and renouncing violence, a bargain for freedom.

Finally, after spending ten years in the cellular jail and writing many mercy petitions, Savarkar, along with his brother, was shifted to a prison in Ratnagiri in 1921, before his subsequent release in 1924 on the condition of the confinement of his movements to the Ratnagiri district and his non-participation in political activities. These restrictions were lifted only in 1937.

The accounts of the Andaman jail, however, expose this perfidy, even as they show that there was little veerta (bravery) in the so-called “Veer Savarkar”.

Jaywant Joglekar, who authored a book euologising Savarkar as ‘Father of Hindu Nationalism argued that the promises he made about his love and loyalty to the British, about his readiness to serve the government in any capacity required and so on were a part of a tactical ploy – perhaps one inspired by Shivaji – employed to make his way out of prison so that he could continue his freedom struggle.[5]

However, history has proven him to be a man of ‘honour’, who stood by the promise he made to the colonial government. How then, one might wonder, did Savarkar acquire the title ‘Veer’?

A book titled Life of Barrister Savarkar authored by Chitragupta was the first biography of Savarkar, published in 1926. Savarkar was glorified in this book for his courage and deemed a hero. And two decades after Savarkar’s death, when the second edition of this book was released in 1987 by the Veer Savarkar Prakashan, the official publisher of Savarkar’s writings, Ravindra Ramdas revealed in its preface that “Chitragupta is none other than Veer Savarkar”.

In this autobiography masquerading as a biography written by a different author, Savarkar assures the reader that:

“Savarkar is born hero, he could almost despise those who shirked duty for fear of consequences. If once he rightly or wrongly believed that a certain system of Government was iniquitous, he felt no scruples in devising means to eradicate the evil.”

Without mincing words in the name of modesty or moderating the use of adjectives in the name of literary minimalism, Savarkar wrote that Savarkar “seemed to posses no few distinctive marks of character, such as an amazing presence of mind, indomitable courage, unconquerable confidence in his capability to achieve great things”. “Who,” he asked about himself, “could help admiring his courage and presence of mind?”

The sectarian mindset, which eventually culminated into the articulation of Hindutva ideology, was evident – as Jyotirmaya Sharma has demonstrated in Hindutva: Exploring the Idea of Hindu Nationalism – in the early Savarkar, that too from a tender age. Only a boy of 12, Savarkar, leading a pack of his schoolmates, attacked a mosque in the aftermath of the Hindu-Muslim riots in Bombay and Pune in 1894-95. Holding back the Muslim boys of the village using “knives, pins and foot rulers”, Savarkar and his friends mounted their attack, “showering stones on the mosque, shattering its windows and tiles”. Recollecting the incident, he later wrote, “We vandalised the mosque to our heart’s content and raised the flag of our bravery on it.” When the news of Hindus killing Muslims in the riots and its aftermath reached him, little Savarkar and his friends “would dance with joy”.[6]

The sectarian nature of Savarkar’s social and political thinking not only bred in him a deep-rooted resentment against Muslims but also clouded his understanding of historical events, leading him to perceive the 1857 War of Indian Independence as retaliation by Hindus and Muslims against Christianity, in response to Britain’s efforts to Christianise India. In his 1909 book, The War of Independence of 1857, published during his revolutionary days, years before he had declared his loyalty to the British government, Savarkar wrote, quoting Justin McCarthy, “The Mahomedan and the Hindu forgot their old religious antipathies to join against the Christian.”[7]p.56

What was to stop the British government, which had passed a law against the practice of Sati (widow burning), from meddling further with Hindu customs by passing a law against idolatry, he asked. After all, “[t]he English hated idolatry as much as they did suttee.” Describing a process he perceived to be the destruction of Hinduism and Islam in India, Savarkar wrote in his book:

“The Sirkar (government) had already begun to pass one law after another to destroy the foundations of the Hindu and Mahomedan religions. Railways had already been constructed, and carriages had been built in such a way as to offend the caste prejudices of the Hindus. The larger mission schools were being helped with huge grants from the Sirkar. Lord Canning himself distributed thousands of Rupees to every mission, and from this fact it is clear that the wish was strong in the heart of Lord Canning that all India should be Christian.”[7]p.57-58

The sepoys, according to Savarkar, were the primary targets in this mission to spread Christianity in India. “[I]f any Sepoy accepted the Christian religion he was praised loudly and treated honourably; and this Sepoy was promoted in the ranks and his salary increased, in the face of the superior merits of the other Sepoys!”[7]p.59

“Everywhere”, he argued, “there was a strong conviction that the Government had determined to destroy the religions of the country and make Christianity the paramount religion of the land”. By thus giving religion an unwarranted centrality in his analysis of the causes of the rebellion, Savarkar, says Jyotirmaya Sharma, expressed jubilation in his accounts of the rebellion “at every instance of a church being felled, a cross being smashed and every Christian being ‘sliced’.”[8]

While the seeds of communalism had been sown in his mind at a very young age, the poison fruit of Hindutva ideology was to blossom only in his late 20s, after Savarkar’s will to fight the British (or the Christians, as he often referred to them in his book on the 1857 uprising) had been defeated during his imprisonment. It was during his last few years of imprisonment that Savarkar first articulated the concept of Hindutva in his book, Essentials of Hindutva, which was published in 1923 and reprinted as “Hindutva: Who Is a Hindu?” in 1928. This ideology was a deeply divisive one which had the potential to distract attention from the British and cast it on Muslims instead.

While he was careful to specify that Hindutva, or ‘Hinduness’, was different from Hinduism and encompassed a wide range of cultures including, among others, the “Sanatanists, Satnamis, Sikhs, Aryas, Anaryas, Marathas and Madrasis, Brahmins and Panchamas”, he nonetheless made it a point to warn that it “would be straining the usage of words too much – we fear, to the point of breaking – if we call a Mohammedan a Hindu because of his being a resident of India.”[9]p.30

“Mohammedan or Christian communities”, he argued, “do not look upon India as their Holyland”. A cohesive nation, according to Savarkar, can ideally be built only by those people who inhabit a country which is not only the land of their forefathers, but “also the land of their Gods and Angels, of Seers and Prophets; the scenes of whose history are also the scenes of their mythology.”[9]p.52

The love and loyalty of Muslims, he warned, “is, and must necessarily be divided between the land of their birth and the land of their Prophets… Mohammedans would naturally set the interests of their Holyland above those of their Motherland”.[9]p.52

One might wonder whether this line of reasoning implies that Muslims cannot be nationals of Pakistan or Afghanistan either, because they would place the interests of Saudi Arabia, wherein lie Mecca and Madina, above the interests of their own country.

Back in the 1920s, the damage that could be done to the freedom movement by his ideology did not fail to come to the notice of the colonial government. Even though Savarkar was released on condition that he should not participate in political activities, he was allowed by the British to organise the Ratnagiri Mahasabha, which undertook what is in today’s lingo called “Ghar Wapsi” and played music in front of mosques while prayers were on.

He was also allowed to meet Keshav.B. Hedgewar, a disillusioned Congressman, who, inspired by his ideology of Hindutva, intended to discuss with him a strategy for creating a Hindu Rashtra. A few months after this meeting, in September 1925, Hedgewar founded the RSS, a communal organisation which, like Savarkar, remained subservient to the British.

In spite of the blanket ban on political participation, Shamsul Islam pointed out:

“The British rulers naturally overlooked these political activities as the future of colonial rule in India rested on the communal divide and Savarkar was leaving no stone unturned in aggravating the Hindu-Muslim divide.”[10]

Savarkar was elected as the president of Hindu Mahasabha in 1937, the year the when the Indian National Congress won a landslide victory in the provincial elections, decimating both the Hindu Mahasabha and that other communal party, the Muslim League, which failed to form a government even in Muslim-majority regions.

But just two years later, the Congress the Congress ministries resigned in protest, when at the outbreak of the Second World War, the viceroy, Lord Linlithgow, declared India to be at war with Germany without any consultation.

This led to the Hindu Mahasabha, under Savarkar’s presidency, joining hands with the Muslim League and other parties to form governments, in certain provinces. Such coalition governments were formed in Sindh, NWFP, and Bengal.

In Sindh, Hindu Mahasabha members joined Ghulam Hussain Hidayatullah’s Muslim League government. In Savarkar’s own words,

“Witness the fact that only recently in Sind, the Sind-Hindu-Sabha on invitation had taken the responsibility of joining hands with the League itself in running coalition government”[11][12]

In the North West Frontier Province, Hindu Mahasabha members joined hands with Sardar Aurangzeb Khan of the Muslim League to form a government in 1943. The Mahasabha member of the cabinet was Finance Minister Mehar Chand Khanna.[13][14]

In Bengal, Hindu Mahasabha joined the Krishak Praja Party led Progressive Coalition ministry of Fazlul Haq in December 1941.[15] Savarkar appreciated the successful functioning of the coalition government.[12][16]

In December 1939, addressing the Mahasabha’s Calcutta session, Savarkar urged all universities, colleges and schools to “secure entry into military forces for youths in any and every way.” When Gandhi had launched his individual satyagraha the following year, Savarkar, at the Mahasabha session held in December 1940 in Madura, encouraged Hindu men to enlist in “various branches of British armed forces en masse.”[17]

In 1941, taking advantage of the World War, Subhas Ch. Bose had begun raising an army to fight the British by recruiting Indian prisoners of war from the British army held by the Axis powers – efforts which eventually culminated in his invasion of British India with the help of the Japanese military. During this period, addressing the Hindu Mahasabha session at Bhagalpur in 1941, Savarkar told his followers,

” it must be noted that Japan’s entry into the war has exposed us directly and immediately to the attack by Britain’s enemies…Hindu Mahasabhaites must, therefore, rouse Hindus especially in the provinces of Bengal and Assam as effectively as possible to enter the military forces of all arms without losing a single minute.”

In reciprocation, the British commander-in-chief, “expressed his grateful appreciation of the lead given by Barrister Savarkar in exhorting the Hindus to join the forces of the land with a view to defend India from enemy attacks,” according to Hindu Mahasabha archives perused by Shamsul Islam.

In response to the Quit India Movement launched in August 1942, Savarkar instructed Hindu Sabhaites who were “members of municipalities, local bodies, legislatures or those serving in the army… to stick to their posts,” across the country. At that time, when Japan had conquered many Southeast Asian countries in India’s vicinity, Bose was making arrangements to go from Germany to Japan – from whose occupied territories the INA’s assault on British forces was launched in October the following year.

It was under these circumstances that Savarkar not only instructed those serving in the British army to ‘stick to their posts’, but had also been involved for years in “organising recruitment camps for the British armed forces which were to slaughter the cadres of INA in different parts of North-East later.” In one year alone, Savarkar had boasted in Madura, one lakh Hindus were recruited into the British armed forces as a result of the Mahasabha’s efforts.[18]

Following the assassination of Gandhi on 30 January 1948, police arrested the assassin Nathuram Godse and his alleged accomplices and conspirators. He was a member of the Hindu Mahasabha and of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh. Godse was the editor of Agrani – Hindu Rashtra, a Marathi daily from Pune which was run by the company “The Hindu Rashtra Prakashan Ltd” (The Hindu Nation Publications). This company had contributions from such eminent persons as Gulabchand Hirachand, Bhalji Pendharkar and Jugalkishore Birla. Savarkar had invested ₹ 15000 in the company. Savarkar, a former president of the Hindu Mahasabha, was arrested on 5 February 1948, from his house in Shivaji Park, and kept under detention in the Arthur Road Prison, Bombay. He was charged with murder, conspiracy to murder and abetment to murder.

According to Larry Collins and Dominique Lapierre’s book, Freedom at Midnight, written based on information acquired from in-depth interviews and extensive research of official documents including police records.

“Bombay, 4 January 1948. Three men who wanted Gandhi to die stood in the darkness before an iron grille barring the entrance to a tawdry two storey building of weather-beaten cement in the northernmost suburb of Bombay. The only trace of elegance on its fagade was a marble plaque sealed into one wall. It denotedin Mahratti the building’s functibn: Savarkar Sadan – Savarkar’s House.” [19a] p.481

On January 14, 1948, three members of the Hindu Mahasabha – Nathuram Godse, Narayan Apte and Digambar Badge, an arms dealer regularly selling weapons to the Mahasabha – arrived at Savarkar Sadan in Bombay. Apte and Godse were among the very few who “had the right to move immediately past that room up a flight of stairs to the personal quarters of the dictator of the Hindu Rashtra Dal.

Badge, who did not have such unrestricted access to Savarkar, was told to wait outside. Apte took from him the bag containing gun-cotton slabs, hand grenades, fuse wires and detonators, and went inside with Godse. When the duo returned to Badge after 5-10 minutes, Apte was still carrying with him the bag of weapons, which he asked Madanlal Pahwa and his seth, Mahasabha member Vishnu Karkare, to carry with them to Delhi.

Both Pahwa and Karkare had already visited Savarkar before Godse and Apte arrived at Savarkar Sadan with the weapons that day. According to Collins and Lapierre:

“A guard showed the trio into Savarkar,s cluttered receptiroom. Very few people had the right to move immediately past that room up a flight of stairs to the personal quarters of the dictator of the Hindu Rashtra Dal. Nathuram Godse and Narayan Apte were among them. Digamber Badge was not and so, taking Badge’s tabla, they went upstairs without him.

Godse, Apte and Badge were not the first of their little group to penetrate the headquarters of Veer Savarkar that January day. Earlier, Karkare had ushered Madanlal into the master’s presence. Karkare had described the young punjabi ‘as a very daring worker’. Savarkar’s response was to bestow one of his glacial smiles on Madanlal. Then he had caressed his bare

forearm as a man might stroke a kitten’s back. ‘Keep up the good work,’ he had urged.

Their meeting with Savarkar finished, the trio split up for the night. Badge went to the common dormitory of the Hindu Mahasabha. Apte and Godse, the two Chitpawan Brahmins, left for a more becoming destination, the Sea Green Hotel.

As soon as they’d reached the hotel the irrepressible Apte made a telephone call. The number he requested was the last in the world which one would have expected from the man vowed to commit India’s crime of the century. It was the central switchboard of the Bombay Police Department. When

the switchboard answered, Apte requested extension 3o5. There at the other end of the line was the welcoming voice of the girl who would share Apte’s bed that evening, the daughter of the Chief Surgeon of the Bombay Police.” [19]p. 482

The first attempt to assassinate Gandhi at Birla House occurred on 20 January 1948. According to Stanley Wolpert, Nathuram Godse and his colleagues followed Gandhi to a park where he was speaking.[20] One of them threw a grenade away from the crowd. The loud explosion scared the crowd, creating a chaotic stampede of people. Gandhi was left alone on the speakers’ platform. The original assassination plan was to throw a second grenade, after the crowds had run away, at the isolated Gandhi.[18] But the alleged accomplice Digambar Badge lost his courage, did not throw the second grenade and ran away with the crowd. All of the assassination plotters ran away, except Madanlal Pahwa who was a Punjabi refugee of the Partition of India. He was arrested.[20]. The rest of the conspirators began their run from Delhi.

“Madanlal was still loyal to his fellow conspirators,” Collins and Lapierre wrote.

“Madanlal was still loyal to his fellow conspirators. Despite the fact he alone had acted, he was sure they would try again. He was determined to win them as much time as he could by refusing to talk. Nonetheless, at the very beginning he yielded a vital piece of information. He admitted he was not a crazy Punjabi refugee acting alone, but one of a group of killers. He gave the number of people involved, seven. ..

Then, calculating that the others had by now had time to flee, he gave a harmless account of their activities in Delhi. Suddenly, in a moment of self-assertion, he gave the police a second clue. He admitted he had been at Savarkar Sadan with his associates and boasted he had personally met the famous political figure. The police then forced him to describe each of his fellow conspirators. His descriptions were not very helpful. He gave only one name, Karkare’s, and managed to give it wrong: ‘Kirkree.’

His description of Godse, however, contained a third vital scrap of information. He gave his occupation. He said he was the ‘editor of the Rashtriya or Agrani Marhatta language newspaper’. The name of the paper was incomplete and misspelled, but those words were still the most precious scrap of information the police could have had.

While the interrogation continued, police rushed off to search the Hindu Mahasabha and the Marina Hotel’ They found no one. Badge and his servant were miles away on a train heading for Poona. Karkare and Gopal Godse were registered under false names in a hotel in Old Delhi. Apte and

Nathuram Godse had disappeared”from the Marina hours before. On the desk of Room 40, however, the police found a fourth vital clue. It was a document denouncing the agreement produced by Delhi’s leaders to get Gandhi to end his fast. The man whose signature it bore, Ashutosh Lahiri, an official of the Hindu Mahasabha, had known Apte and Godse well for

eight years. He knew well they were the administrator and editor of a Savarkarite Marhatta newspaper called the Hindu Rashtra.

At midnight the police ended their interrogation of Madanlal for the night and closed their first daily register of the case. They had every reason to be satisfied with the results of their seven hours’ work. They knew they were faced with a plot. They knew how many people were involved. They knew it

involved followers of Veer Savarkar… ” [19]p. 517-518

On January 30, 1948 at 5 p.m, As Gandhi was walking briskly up the steps leading to the lawn, an unidentified man in the crowd spoke up, somewhat insolently in Reiner’s recollection, “Gandhiji, you are late”. Gandhi slowed down his pace, turned toward the man, and gave him an annoyed look. But no sooner had Gandhi reached the top of the steps, than another man, a stocky Indian man, in his 30s, and dressed in khaki clothes, stepped out from the crowd and into Gandhi’s path. He soon fired several shots up close, at once felling Gandhi.

According to Ashis Nandy, before firing the shots Godse “bowed down to Gandhi to show his respect for the services the Mahatma had rendered the country; he made no attempt to run away and himself shouted for the police”.[21] According to Pramod Das, Godse after firing the shots raised his hand with the gun, surrendered and called for the police.[22]

Along with Nathuram Godse many other accomplices were arrested. They were all identified as prominent members of the Hindu Mahasabha. Along with Godse and accomplices, police arrested the 65-year-old Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, who they accused of being the mastermind behind the plot.

The accused, their place of residence and occupational background were as follows:[23]

Savarkar was arrested on 5 February 1948, from his house in Shivaji Park, and kept under detention in the Arthur Road Prison, Bombay. He was charged with murder, conspiracy to murder and abetment to murder. A day before his arrest, Savarkar in a public written statement, as reported in The Times of India, Bombay dated 7 February 1948, termed Gandhi’s assassination a fratricidal crime, endangering India’s existence as a nascent nation. The mass of papers seized from his house had revealed nothing that could remotely be connected with Gandhi’s murder. Due to lack of evidence, Savarkar was arrested under the Preventive Detention Act.

On the February 22, Savarkar gave to the Indian government the same undertaking he had once given to the British Raj:

“I shall refrain from taking part in any communal or political activity for any period the government may require in case I am released on that condition.”

Sardar Vallabhai Patel – then the deputy prime minister and Union home minister, and now a figure claimed by the Hindu Right as their own – was the chief prosecutor of the case.

Patel wrote to Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru on February 27, 1948, less than a month after Gandhi’s assassination,

“…The RSS was not involved at all. It was a fanatical wing of the Hindu Mahasabha directly under Savarkar that hatched the conspiracy…”

But he added,

“His assassination was welcomed by those of the RSS and the Mahasabha who were strongly opposed to his (Gandhi’s) way of thinking…”

Patel was convinced of Savarkar’s guilt. However, personal conviction would not compromise Patel’s commitment to due legal process. Allaying Mahasabha leader Syama Prasad Mookerjee’s concern that Savarkar “was being prosecuted on account of his political convictions,” Patel wrote a letter to him 20 days before Savarkar was named in the chargesheet, explaining,

“I have told (the Advocate-General and other legal advisers and investigating officers), quite clearly, that the question of inclusion of Savarkar must be approached purely from a legal and judicial standpoint and political considerations should not be imported into the matter… I have also told them that, if they come to the view that Savarkar should be included, the papers should be placed before me before action is taken.”

When Syama Prasad Mookerjee wrote to him in July 1948 regarding the ban on the RSS and the “disloyalty” of some Muslims, Patel criticised the RSS,

“The activities of the RSS constituted a clear threat to the existence of the government and the state.” [24]

Godse claimed full responsibility for planning and carrying out the assassination. However, according to the Approver Digambar Badge, on 17 January 1948, Nathuram Godse went to have a ‘last darshan’ with Savarkar in Bombay before the assassination. While Badge and Shankar waited outside, Nathuram and Apte went in. On coming out Apte told Badge that Savarkar blessed them “Yashasvi houn ya” (be successful and return). Apte also said that Savarkar predicted that Gandhi’s 100 years were over and there was no doubt that the task would be successfully finished.[25][26]

The trial began on 27 May 1948 and ran for eight months before Justice Atma Charan passed his final order on 10 February 1949. The prosecution called 149 witnesses, the defense none. The court found all of the defendants except one guilty as charged. Eight men were convicted for the murder conspiracy, and others convicted for violation of the Explosive Substances Act. Savarkar was acquitted and set free due to lack of evidence. Nathuram Godse and Narayan Apte were sentenced to death by hanging and the remaining six (including Godse’s brother, Gopal) were sentenced to life imprisonment.

Evidence found against Savarkar in Badge’s testimony included: [27]

Savarkar, in his skilful defence, pointed out that the meeting of Godse and Apte with Savarkar on January 14 cannot be established from Badge’s account, because he did not claim to witness the meeting itself. His account only mentioned that on the 14th, he arrived at Savarkar Sadan with Apte and Godse, where he was made to wait outside, while the two went in. Savarkar argued:[27]

“Firstly…visiting Savarkar Sadan does not necessarily mean visiting Savarkar. Apte and Godse were well acquainted with Damle, Bhinde and Kasar who were always found there (in Savarkar Sadan)… So Apte and Godse might have gone to see their friends and co-workers in Hindu Mahasabha.”

After thus drawing other members of Hindu Mahasabha into the line of fire for his defence, Savarkar then went on to say, “Secondly… Apte and Godse deny it and state that they never went with Badge and the bag (of weapons) to Savarkar Sadan as alleged.”

With regards to Badge’s claim about Apte informing him that Savarkar had decided that Gandhi had to be assassinated, Savarkar said in his defence:

“..taking it for granted that Badge himself is telling the truth when he says Apte told him this sentence, the question remains whether what Apte told Badge is true or false. There is no evidence to show that I had ever told Apte to finish Gandhi, Nehru and Suhrawardy. Apte might have invented this wicked lie to exploit Savarkar’s moral influence on the Hindu Sanghatanists for his own purposes. It is the case of the prosecution itself that Apte was used to resort to such unscrupulous tricks. For example, Apte is alleged to have given false names and false addresses to hotel keepers.. and collected arms and ammunition secretly..”

After thus attacking Apte, who refused till the very end to admit in court that Savarkar had anything to do with the conspiracy, Savarkar then pointed out that in any case both Apte and Godse deny having told Badge that Savarkar had decided that Gandhi had to be assassinated. The same reasoning was again used to defend himself from Badge’s claim of having been told by Apte that Savarkar had predicted Gandhi’s time was up. After thus attacking Apte, who refused till the very end to admit in court that Savarkar had anything to do with the conspiracy, Savarkar then pointed out that in any case both Apte and Godse deny having told Badge that Savarkar had decided that Gandhi had to be assassinated.

The same reasoning was again used to defend himself from Badge’s claim of having been told by Apte that Savarkar had predicted Gandhi’s time was up.

“Firstly, I submit.. that Apte and Godse did not see me on 17th January 1948 or any other day near about and I did not say to them, ‘Be successful and come back’… Secondly, assuming that what Badge says about the visit is true, still as he clearly admits that he sat in the room on the ground floor of my house and Apte and Godse alone went upstairs, he could not have known for certain whether they.. did see me at all or returned after meeting someone of the family of the tenant who also resided on the first floor of the house.”

After thus arguing that his testimony does not establish that Godse and Apte necessarily met him at Savarkar Sadan, he went on to make more concessions:

“Taking again for granted that Apte and Godse did see me and had a talk with me, still it was impossible for Badge to have any personal and direct knowledge of what talk they had with me for the simple reason that he could not have either seen or heard anything happening upstairs on the first floor from the room in which he admits he was sitting on the ground-floor. It would be absurd to take it as a self-evident truth that.. they must have talked to me about some criminal conspiracy only. Nay, it is far more likely that they could have talked about anything else but the alleged conspiracy.”

With regards to Badge’s testimony that he saw and heard Savarkar wishing Apte and Godse, “be successful and come back”, Savarkar told the court:

“Even if it is assumed that I said this sentence it might have referred to any objects and works.. Such as the Nizam Civil Resistance, the raising of funds for the daily paper, Agrani, or the sale of the shares of Hindu Rastra Prakashan Ltd.. or any other legitimate undertaking. As Badge knew nothing as to what talk Apte and Godse had with me upstairs, he could not assert as to what subject my remark “Be successful etc’ referred.”

Justice Charan found Badge’s testimony convincing and pointed out:[27]

“(Badge) gave his version of the facts in a direct and straightforward manner. He did not evade cross-examination or attempt to evade or fence with any question. It would not have been possible for anyone to have given evidence so unfalteringly stretching over such a long period and with such particularity in regard to the facts which had never taken place. It is difficult to conceive of anyone memorising so long and so detailed a story if altogether without foundation.”

The trial court judge, Justice Atma Charan thought Badge was a “truthful witness”, but exonerated Savarkar only because there was no corroborative evidence in support of the approver’s deposition.

This was also because Godse and others did their best to ensure their mentor wasn’t implicated in the assassination case. For instance, Godse made out that his relationship with Savarkar wasn’t beyond what a leader has with followers.

Godse said that he and others decided in 1947 to “bid goodbye to Veer Savarkar’s lead and cease to consult him in our future policy and programme… I re-assert that it is not true that Veer Savarkar had any knowledge of my activities which ultimately led me to fire shots at Gandhiji.”

The prosecution had harped on Godse and Apte’s devotion to Savarkar. Savarkar, as was his habit, disowned them:

“Many criminals cherish high respect to the Gurus and guides of their religious sects… But could ever the complicity of the Guru or guide in the crimes of those of his followers be inferred and held proved only on the ground of the professions of loyalty and respect to their Gurus of those criminals?”

“Nathuram was deeply hurt by Tatyarao’s [Savarkar’s] calculated, demonstrative non-association with him either in court or in Red Fort Jail,” wrote P.L. Inamdar in his memoirs, The Story of the Red Fort Trial, 1948-49. The lawyer who defended two of the co-conspirators – including Nathuram’s brother, Gopal Godse – told his readers,

“How Nathuram yearned for a touch of Tatyarao’s hand, a word of sympathy, or at least a look of compassion in the secluded confines of the cells. Nathuram referred to his hurt feelings in this regard even during my last meeting with him at the Simla High Court.”[28]

But during the trial, Savarkar did not even turn “his head towards.. Nathuram.. much less speak with him,” Inamdar wrote.

“While the other accused freely talked to each other exchanging notes or banter, Savarkar sat there sphinx-like in silence, completely ignoring his co-accused in the dock, in an unerringly disciplined manner.”[28]

Commenting on Savarkar’s conduct during the trails, Noorani, whose academic preoccupation is the study of the trials of Indian political figures, wrote in his authoritative book Savarkar and Hindutva: The Godse Connection,

“The annals of great trials provide hardly a parallel in cowardice and deceit.”[29]

Seventeen years after Godse was hanged, Savarkar, then aged almost 83, renounced food and medicine in the beginning of February 1966 and died on February 26. But the truth about his role in Gandhi’s murder was not cremated with his body. Only three years later, evidence found by the Kapur Commission implicated Savarkar in Gandhi’s murder.

On 12 November 1964, a religious programme was organized in Pune, to celebrate the release of the Gopal Godse, Madanlal Pahwa, Vishnu Karkare from jail after the expiry of their sentences.

Dr. G. V. Ketkar, grandson of Bal Gangadhar Tilak, former editor of Kesari and then editor of Tarun Bharat, who presided over the function, revealed six months before the actual event, that Nathuram Godse disclosed his ideas to kill Gandhi and was opposed by Ketkar. Ketkar said that he passed the information to Balukaka Kanitkar who conveyed it to the then Chief Minister of Bombay State, B. G. Kher.

The Indian Express in its issue of 14 November 1964, commented adversely on Ketkar’s conduct that Ketkar’s fore-knowledge of the assassination of Gandhi added to the mystery of the circumstances preceding to the assassination. Ketkar was arrested. A public furor ensued both outside and inside the Maharashtra Legislative Assembly and both houses of the Indian parliament. There was a suggestion that there had been a deliberate dereliction of duty on the part of people in high authority, who failed to act responsibly even though they had information that could have prevented Gandhi’s shooting.

Under pressure of 29 members of parliament and public opinion, the then-Union home minister, Gulzarilal Nanda, appointed Gopal Swarup Pathak, M. P. and a senior advocate of the Supreme Court of India, in charge of inquiry of conspiracy to murder Gandhi. Since both Kanitkar and Kher were deceased, the central government intended on conducting a thorough inquiry with the help of old records in consultation with the government of Maharashtra, Pathak was given three months to conduct his inquiry. But as Pathak was appointed a central minister and then governor of Mysore state, the commission of inquiry was reconstituted and Jivanlal Kapur a retired judge of the Supreme Court of India was appointed to conduct the inquiry.

The terms of reference for this inquiry were following [30]:pg.3:

In February 1966, Savarkar voluntarily courted death, by stopping all consumption of food and water. He said it was better for a person to die willingly at the end of his life mission. But did Savarkar take this decision because he wanted to evade the prospect of the commission inflicting ignominy on him late in life?

That question cannot be answered. But it did perhaps free Savarkar’s bodyguard, Appa Ramachandra Kasar, and his secretary, Vishnu Damle, who hadn’t previously testified during his trials, to depose before the commission.

It took three years to complete its work. It strongly indicted those responsible for Gandhi’s security with negligence. It was provided with statements recorded by Bombay police, not produced in the court, especially the testimony of two of Savarkar’s close aides – Mr. Appa Ramachandra Kasar, his bodyguard, and Mr. Gajanan Vishnu Damle, his secretary. Statements of both Mr. Appa Ramachandra Kasar and Mr. Gajanan Vishnu Damle that the commission examined, were already recorded by the Bombay police on 4 March 1948.[30]:pg.317

Their statements not only provided an independent corroboration of the two meetings with Savarkar which Badge had referred to in his testimony, but also revealed that before carrying out the assassination, Godse and Apte had met Savarkar once again on January 23 or 24, after Madanlal Pahwa’s first attempt on Gandhi’s life had failed.

Based on the statements of Savarkar’s bodyguard, Appa Ramchandra, Justice Kapur stated in the commission’s report:

“On or about 13th or 14th January, Karkare came to Savarkar with a Puniabi youth (Madanlal) and they had an interview with Savarkar for about 15 or 20 minutes. On or about 15th or 16th Apte and Godse had an interview with Savarkar at 9.30 P.M. After about a week so, may be 23rd or 24th January, Apte and Godse again came to Savarkar and had a talk with him.. for about haIf an hour.”[30]:pg.317

Statements of Savarkar’s secretary, Gajanan Vishnu Damle, also corroborated the fact that Apte and Godse met Savarkar in the middle of January. Both their statements, as well as Badge’s testimony, indicated that Savarkar had lied before the court when he said, “Apte and Godse did not see me on 17th January 1948 or any other day near about (emphasis added).”[30]:pg.318

Their statements not only established the close working relationship Gode and Apte had with Savarkar since 1946, the report said, but also provided evidence which shows that:

Karkare was also well-known to Savarkar and was also a frequent visitor. Badge also used to visit Savarkar. Dr. Parchure (another accused for whom P.L. Inamdar won an acquittal) also visited him. All this shows that people who were subsequently involved in the murder of Mahatma Gandhi were all congregating sometime or the other at Savarkar Sadan and sometimes had long interviews with Savarkar. It is significant that Karkare and Madanlal visited Savarkar before they left for Delhi and Apte and Godse visited him both before the bomb was thrown and also before the murder was committed and on each occasion they had long interviews.

The commission pointed out various lapses and flaws on part of the Inspector General of Police of Delhi, Sanjivi. The commission remarked summarising the Delhi investigation,

The anxiety of the officialdom in New Delhi, to take any intelligent interest in the investigation in the bomb case is not indicated by any tangible evidence on the investigation in Mumbai the commission observed, After the murder the police suddenly woke up into diligent activity throughout India, of which there was no evidence before the tragedy[31]

According to Noorani, the Kapur Commission was provided with evidence not produced in the court; especially the testimony of two of Savarkar’s close aides – Appa Ramachandra Kasar, his bodyguard, and Gajanan Vishnu Damle, his secretary. The court had earlier exonerated Savarkar for want of corroborative evidence in support of the approver’s confession. However, Justice Kapur’s findings are all too clear. He concluded:

“All these facts taken together were destructive of any theory other than the conspiracy to murder by Savarkar and his group.” [32]

Decades before the goons of the ‘saffron brigade’ have called for digging up Muslim women from their graves and raping them or rape of women during the 2002 Gujarat and 2013 Muzaffarnagar riots, Veer Savarkar justified and supported rape as a legitimate political weapon. This he did by re configuring the idea of “Hindu virtue” in his book Six Glorious Epochs of Indian History, which he wrote in Marathi a few years before his death in 1966.

Six Glorious Epochs provides an account of Hindu resistance to invasions of India from the earliest times. It is based on historical records (many of them dubious), exaggerated accounts of foreign travellers, and the writings of colonial historians. Savarkar’s own febrile and frightening imagination reworks these diverse sources into a tome remarkable for its anger and hatred.

Savarkar’s account of Hindu resistance is also a history of virtues. He identified the virtues that proved detrimental to India and led to its conquest. He expounded his philosophy of morality in Chapter VIII, Perverted Conception of Virtues, in which he rejected the idea of absolute or unqualified virtue.

“In fact virtues and vices are only relative terms,” he said.

It is in this paradigm of ethics that Savarkar supported the idea of rape as a political weapon. He articulated it as a wish, through a question: What if Hindu kings, who occasionally defeated their Muslim counterparts, had also raped their women?

He expressed this wish after declaring, “It was a religious duty of every Muslim to kidnap and force into their religion, non-Muslim women.” He added that this fanaticism was not “Muslim madness”, for it had a distinct design – to increase the “Muslim population with special regard to unavoidable laws of nature.” It is the same law, which the animal world instinctively obeys. [33] p.175

He wrote,

“The Africa n wild tribes of today kill only the males from amongst their enemies, whenever there are tribal wars, but not the females, who are

eventually distribute d by the victor tribes among themselves. To obtain from them future progeny t o increase their numbers is considered by these tribe s to be their sacred duty! ” [33] p.175

Immediately thereafter, he spoke of the well-wishers of Ravana who advised him to return to Rama his wife, Sita, whom he had abducted. They said it was highly irreligious to have kidnapped Sita. Savarkar quotes Ravana saying, “What? To abduct and rape the womenfolk of the enemy, do you call it irreligious? It is Parodharmah, the greatest duty!”

“‘What ?’ cried the wrathful Ravan, “To abduct and rape the womenfolk of the enemy, do yo u call it irreligious? ” Pooh, pooh!

(To carry away the women of others and to ravish them is itself the supreme religious duty)

‘Parodharmah’, the greatest duty !” [33] p.176

“With this same shameless religious fanaticism the aggressive Muslims o f those times considered it their highly religious duty to carry away forcibly the women of the enemy side, as i f they were commonplace property, to ravish them, to pollute them, and to distribute them to all and sundry , from the Sultan to the common soldier and to absorb them completely i n their fold . This was considered a noble act which increased their number. “[33] p.176

Savarkar is venomously critical of Muslim women who, “whether Begum or beggar”, never protested against the “atrocities committed by their male compatriots; on the contrary they encouraged them to do so and honoured them for it”.

Savarkar, even by his own standards, takes a huge leap by claiming that Muslim women living even in Hindu kingdoms enticed Hindu girls, “locked them up in their own houses, and conveyed them to Muslims centres in Masjids and Mosques”.

“Hindu women were considered kafirs and born slaves. So these Muslim women were taught to think it their duty to help in all possible ways, their molestation and forcib le conversion to Islam. No Muslim woman whether a Begum or a beggar, ever protested against the atrocities committed by their male compatriots; on the contrary they encouraged them to do so and honoured them for it . A Muslim woman did everything in her power to harass such captured or kidnapped Hindu women. No t only in the troubled times of war but even in the intervening period s of peace and even when they themselves lived in the Hindu kingdoms, they enticed and carried away young Hindu girls locked them up i n their own houses, or conveyed them to the Muslim centres in Masjids and Mosques. The Muslim women all over India considered it their holy duty to do so.“[33] p.177-178

Muslim women were emboldened to perpetrate such atrocities because they did not fear retribution from Hindu men who, argued Savarkar, “had a perverted idea of women-chivalry”.

“The Muslim women never feared retribution or punishment at the hands of any Hindu for their heinous crime . They had a perverted idea of woman-chivalry. If in a battle the Muslims won, they were rewarded for such crafty

and deceitful conversions of Hindu women; but even if the Hindus carried the field and a Hindu power was established in that particular place (and such incidents in those times were not very rare) the Muslim-men alone, i f at all, suffered the consequential indignities bu t the Muslim women, never!

Only Muslim men, and not women, were taken prisoner. Muslim women were sure that even in the thick of battles and in the confusion wrought just after them neither the victor Hindu Chiefs, nor any of their common soldiers, nor even any civilian would ever touch their hair. For ‘albeit enemies and atrocious, they were women’! Hence, even when they were taken prisoner in battles the Muslim women,—royal ladies as also the commonest slaves,—were invariably sent back safe and sound t o their respective families! Such incidents were common enough in those times. And this act was glorified by the Hindus as their chivalry towards the enemy women an d the generosity of their religion!“[33] p.178

This regret prompts him to criticize Shivaji for sending back the daughter-in-law of the Muslim governor of Kalyan, whom he defeated, as well as Peshwa Chimaji Appa (1707-1740), who did the same with the Portuguese wife of the governor of Bassein.

Savarkar wrote:

“But is it not strange that, when they did so, neither Shivaji Maharaj nor Chimaji Appa should ever remember, the atrocities and the rapes and the molestation, perpetrated by Mahmud of Ghazni, Muhammad Ghori, Allauddin Khalji and others, on thousands of Hindu ladies and girls like the princesses of Dahir, Kamaldevi, the wife of Karnaraj of Karnawati and her extremely beautiful daughter, Devaldevi. Did not the plaintive screams and pitiful lamentations o f the millions of molested Hindu women which reverberated throughout the length and breadth of the country, reach the ears o f Shivaji Maharaj and Chimaji Appa?”[33] p.179

Savarkar’s febrile imagination now flies on the wings of rhetoric.

He writes:

“The souls of those millions of aggrieved women might have perhaps said ‘Do not forget, O Your Majesty Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj and O! Your Excellency Chimaji Appa, the unutterable atrocities and oppression and outrage committed on us by the sultans and Muslim noblemen and thousands of others, big and small.

“Let these sultans and their peers take a fright that in the event of a Hindu victory our molestation and detestable lot shall be avenged on the Muslim women. Once they are haunted with this dreadful apprehension that the Muslim women too, stand in the same predicament in case the Hindus win, the future Muslim conquerors will never dare to think of such molestation of Hindu women.“[33] p.179

Savarkar’s overturned the code of ethics and freed the Hindus from the shackles that prevent them from descending into barbarism. Under a subsection titled, But If, he seeks to hammer in his point. He asks readers:

“Suppose if from the earliest Muslim invasions of India, the Hindus also, whenever they were victors on the battlefields, had decided to pay the Muslim fair sex in the same coin or punished them in some other ways, i.e., by conversion even with force, and then absorbed them in their fold, then? Then with this horrible apprehension at their heart they would have desisted from their evil designs against any Hindu lady.” [33] p.180

He adds:

“If they had taken such a fright in the first two or three centuries, millions and millions of luckless Hindu ladies would have been saved all their indignities, loss of their own religion, rapes, ravages and other unimaginable persecutions.”[33] p.180

Thus, the use of rape as a political weapon stands justified.

Why should Savarkar’s idea of rape as a political weapon apply today, given that Six Glorious Epochs deal with India’s past?

This is because Savarkar very explicitly stated that a change of religion implies a change of nationality.

It was Savarkar, not Muhammad Ali Jinnah, who first categorised Hindus and Muslims as two nations. From the Hindutva perspective, the two nations – Hindu and Muslim – have been locked in a continuous conflict for supremacy since the 11th century.

In the Savarkarite worldview, only those ethical codes should be adhered to which enable the Hindus to establish their supremacy over the Muslims. Thus, he reasoned, it is justified to rape Muslim women in riots because it is revenge for the barbarity of Muslims in the medieval times, whether proven or otherwise. After all, today’s riots are a manifestation of the historical conflict.

Later in Six Glorious Epochs, Savarkar writes:

“O thou Hindu society! Of all the sins and weaknesses, which have brought about thy fall, the greatest and most potent are thy virtues themselves.

Ahimsa (non-violence), kindness, chivalry even towards the enemy women, protection of an abjectly capitulating enemy, (forgiveness, a glorious emblem for the brave!) and religious tolerance were all virtues no doubt— very noble virtues ! But it is blind and slovenly— even impotent— adoption of all these very virtues, irrespective of any consideration given to the propriety of time, place or persons that so horribly vanquished them in the milliennial Hindu-Muslim war on the religious front.”[33] p.187

These virtues were cast aside during the ‘Saffron terrorism’. Some of the incidents are listed below:

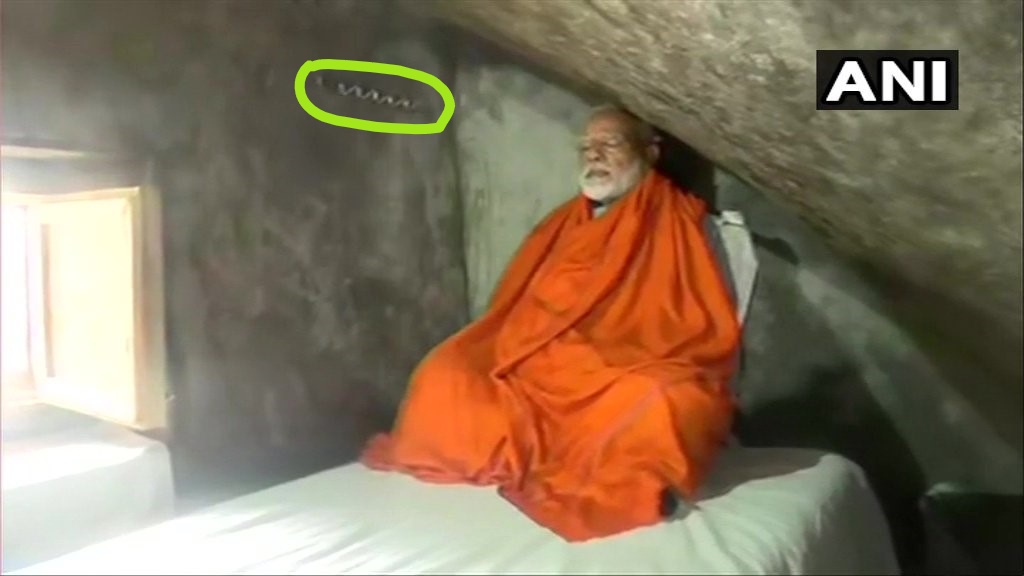

No meditation is complete or meaningful without the right attire, red carpet, room service and of course a stage managed photo opportunity

Fake date of birth?

When do you wish ‘a very happy birthday’ to Modi?

According to the Lok Sabha and Gujarat Assembly websites and Modi’s election affidavits, he was born on September 17, 1950.

But the records at M.N. College of Science in Visnagar, north Gujarat, show a “Narendrakumar Damodardas Modi” as a pre-science (equivalent to Class XII) student and cite his date of birth as August 29, 1949.

Which one is genuine and which one is fake?

Selling tea at Vadnagar railway station at the age of six: Time machine a reality?

Narendra Modi claimed that he sold tea at Vadnagar railway station at the age of six.

Vadnagar station was built in 1973. At that time Modi was at least 23. But PM Modi said he went to the Himalayas at the age of 17, leaving his family behind.

So at the age of six did he use a time machine to fly to 1973, sell tea and then go back to 1955 boarding the same time machine?

Modi: The adventure of the noble bachelor that Holmes would fail solving

Modi spent spent much of his life working for the BJP and a right-wing Hindu organisation that puts a prize on celibacy. He portrayed his single status as a virtue while campaigning.

In 2014, as Modi filed his papers to stand as a member of parliament from the Vadadora constituency in Gujarat, he acknowledged that he had a wife. He wrote the name “Jashoda” in a column regarding his marital status. He said he had no details as to her address.

Modi has four times contested seats in Gujarat’s regional assembly but has never given his marital status on the affidavits before 2014.

Was he suffering from amnesia about his marriage or is he an incorrigible liar? Holmes would fail to solve that mystery

Who stole the gold jewelries and money on the night Modi left his house?

Modi said that heleft his house at the age of 18 to walk on the path of spirituality. He spent meditating for three years on Himalayas.

On the same night money and gold jewelries were stolen from their house and an FIR was filed in Vadnagar P.S. Modi’s father died in a shock.

Who stole the money and gold?

Modi’s educational qualification

Amit Shah and Arun Jaitley presenting copies of marksheets and degree certificates awarded to Modi. (Credit PTI file)

Amit Shah and Arun Jaitley presenting copies of marksheets and degree certificates awarded to Modi. (Credit PTI file)here are serious questions over the authenticity of PM Modi’s BA degree from the University of Delhi and MA degree from the Gujarat University. Though both the universities have released statements to support Modi’s claim in the past, they continue to refuse to share the information needed to allay growing suspicion over various anomalies present in the available documents- his name, date of birth and even his specialisation on a subject called “Entire Political Science”.

Taking the plea that the matter is sub judice, universities ignore to respond to queries.

There are six anomalies that give credence to the charge that the PM’s degrees may be fake:

1. Multiple entries of date of birth

As the storm around Modi’s degree started to brew, a prominent newspaper carried similar reports with quotes from unnamed PMO sources and a photo of Modi’s MA degree.

The matter would have been put to rest, but for the fact that according to this reported degree, Modi’s date of birth is August 29, 1949 as opposed to the officially stated date – September 17, 1950.

This same MA degree was presented by the BJP. It can’t be passed of as a mistake due to carelessness as every entry – the day, month and year – is different.

2. Different name and year of attendance

In Modi’s BA marksheet, his name is shown as Narendra Kumar Damodardas Modi, while in Modi’s BA and MA degrees, his name reads as “Narendra Damodardas Modi”. This discrepancy wouldn’t have raised an eyebrow if there was a corresponding change of name affadavit, but no such document has been made public.

Surely, in the interest of transparency and confidence in integrity of holders of public offices we deserve an explanation as to why this mismatch exists.

The tale of mismatches doesn’t end here. Even in the year of attending the course, there is discrepancy. While Modi’s marksheet shows 1977 as his final year in college, the same is shown as 1978 in what has been presented as his BA degree.

3. Suspicious name of the course

The MA degrees of the PM that have been made public show the specialisation as “Entire Political science”.

Now political science is a known discipline, but where does “entire” fit in? This suspicious name adds to the mystery surrounding his degrees. Also, it has been alleged that the college from which he obtained his MA has no political science course. Again, all this may amount to nothing, but like other instances, Modi’s silence here is only making things look worse.

4. Where are PM Modi’s classmates?

Since Modi is the most prominent public figure in India today, it shouldn’t have been difficult to find people who attended the course or took the exam with him. Even while attending normal courses, multiple acquaintances are made in college, but since Modi is a celebrity and the biggest one at that, hordes of batchmates should have come forward to confirm with pride that they attended a course with him.

However, till date, we are yet to come across even one batchmate who can verify Modi’s degree claim. This is another puzzling and disconcerting aspect that gives credence to the naysayers.

5. Why is his alma mater hiding information?

For any institute, it is a matter of pride to share that famous personalities have been affiliated with them. This helps the institute gain publicity and improve their image, and thereby help attract better students to strengthen the institution’s present and future. This is why Punjab university never grows tired of flaunting its association with former PM Manmohan Singh.

Not only does PU publicise that Manmohan was a gold medalist from PU, it also created a chair in Manmohan Singh’s name and now has enlisted him in professorial capacity. So it’s surprising that both the institutes where Modi claims to have done his higher studies have been so coy about their association with the PM. Their suspicious secrecy around the whole issue seems to have been at Modi’s behest as if they fear to reveal anything that may contradict their boss’ (Modi) claim.

6. The certificate looks suspicious

In the mark sheets released during the that time, name, subjects and marks obtained by the student are hand written, but in the mark sheet of Modi released by the BJP, all these are not handwritten, but printed.

Mark sheets of that year also have signatures of the competent authorities under the heads, ‘Checked By’ and ‘Prepared By’, but Modi’s mark sheet has been signed off only under the head ‘Checked by’ and but the signatures under the head ‘Prepared by‘ is missing.

In the mark sheets of Mr Modi for all the years 1975, 1976, 1977 and 1978 a digit 2366 is written by hand at the top right corner. How this digit is written in all the mark sheets in same handwriting. Is this a clinching evidence that the mark sheet has been forged.

In the mark sheets of that time ‘University of Delhi’ is written in simple font, whereas, in Modi ji’s mark sheet ‘University of Delhi’ is written in modern font, a font that Microsoft petented in 1992. How is it possible?

Modi’s mark sheet appears to be computer generated. Did the Delhi University have computers in 1975? Modern fonts have been used in Modi ji’s mark sheet. Were these fonts available in 1975? Did Bill Gates send a special computer at that time to print Modi’s degrees?

A mystery that even Sherlock Holmes would fail to solve. Or am I wrong? Everything is clear as daylight?

Not only in a democratic country like India, ethically and legally the prime minister’s educational qualifications should be above suspicion. It is also critical to restore faith in the functioning of the university system of the country and instil trust in the genuineness of its degrees.

While the university authorities and investigative agencies seem to be under political pressure not to pursue this allegation of fraud, the reluctance of the media to investigate this matter with vigor and courage is very puzzling as well as disturbing.

Now when nothing from the date of birth to the name to the year of the course is in order, one can’t help but feel there is something fishy regarding the whole claim. A prima facie case has been established and the onus now rests on PM Modi to restore the nation’s confidence in his credibility. It won’t suffice to shoot the messenger and make light of the alleged crime. A fraud is a fraud. The question is not of how educated or not our PM is. The question is whether the nation deserves to be in the know of its PM’s educational attainment. Should India be cheated when it comes to such information?

It’s said Caeser’s wife should be above suspicion, but here Caesar himself is under suspicion.

If the PM can cheat and trick when it comes to his degree, can we guarantee that he won’t cheat or commit fraud in other matters? The trust and credibility of the most important public office of the world’s largest democracy is sacrosanct. So it’s essential that the cloud over Modi’s degree is cleared either way, sooner than later.

Also, we can’t just wait for him to come out clean. The fourth pillar of democracy – Indian media – deserves to do its job of scrutinising the matter with more vigour and courage than it has displayed so far.

It is inexplicable why the media has not undertaken an independent investigation into the whole affair. Its silence makes one fear that the worst may be true.

Shanti Devi was born on December 11, 1926 in a little known town of Delhi. She did not speak much until she reached the age of 4 but otherwise she was just a normal girl like any other in the locality.

At the age of four, the little girl started claiming that the home where she lived was not her real home and that her parents were not her real parents and began to claim to remember details of her past life.

Discouraged by her parents, she ran away from home at age six, trying to reach Mathura. Back home, she stated in school that she was married and had a son with her husband. She said that her husband lived in Mathura (145 kilometers from Delhi) but never uttered his name.

Interviewed by her teacher and headmaster, she used words from the Mathura dialect and said that her husband was a cloth merchant. Shanti Devi told that not only was she married but that she died 10 days after child birth.

That little girl even mentioned three distinctive features of her husband. She said that her husband wore reading glasses, had a wart on left cheek and was a fair skinned man.

The headmaster located a merchant by that name in Mathura who had lost his wife, Lugdi Devi, nine years earlier, ten days after having given birth to a son.

Kedar Nath also said in the reply that Pandit Kanjimal – one of his relatives lived in Delhi and should be allowed to meet Shanti Devi.

Pandit Kanjimal personally met Shanti Devi and was surprised to find the amount of details she gave about Kedar Nath. Thus, he (Kanjimal) arranged for Shanti Devi’s and Kedar Nath’s meeting. Kedar Nath did come along with his and Ludgi’s son and his present wife.

Kedar Nath was however posed as elder brother of himself but Shanti Devi recognized him immediately and also his son Navneet Lal and even pointed out to her mother the fair color of Kedar Nath and the wart on his left cheek.

As she knew several details of Kedar Nath’s life with his wife, he was soon convinced that Shanti Devi was indeed the reincarnation of Lugdi Devi.

The case was brought to the attention of Mahatma Gandhi who set up a commission to investigate; a report was published in 1936.

The commission traveled with Shanti Devi to Mathura, arriving on 15 November 1935. The commission’s report concluded that Shanti Devi was indeed the reincarnation of Lugdi Devi.

In February 1936, Shri Bal Chand Nahata, a rationalist and staunch disbeliever, interrogated Shanti Devi and some related persons. He published his report in the form of a small booklet in Hindi entitled Punarjanma Ki Parayyalochana. He concludes his brief study by saying: “Whatever material that has come before us, does not warrant us to conclude that Shanti Devi has ‘former life recollections or that this cases proves reincarnation.”

Two further reports were written at the time, one critical of the reincarnation claims, and the other, a rebuttal. It’s “Sen, Indra. “Shantidevi Further Investigated”. Proceedings of the India Philosophical Congress. 1938”. Indra Sen MA, LL.B., PH.D was a devotee of Sri Aurobindo and The Mother [since 1934], psychologist, author, and educator, and the founder of Integral Psychology as an academic discipline. So he can’t be unprejudiced. Still here is what I found about his argument: Dr. Indra Sen had also made a close study of the case. He took Shanti Devi to Mathura and Brindaban and “tested her memories on new points.” In April 1939 he secured the cooperation of a hypnotist and, “attempted to get her recollection of her former life in a hypnotic state.” Dr. Sen wrote, “I am confident that Shanti has certain memories which are not of ‘here and now’.” Doesn’t sound like someone who is sure of it. This however can be explained by modern science [under hypnosis human brain can recall all sort of information, known from stories, books…]

In July 1939 Mr. Sushil Bose interrogated Shanti Devi and her father in Delhi and Kedarnath Choube at Mathura. He has reported the interviews in complete details, but has not expressed his own opinion or comments about the case. [If you discover person who is a proof of reincarnation, would you keep calm or would you share it with the world?! ] Bose also interrogated Shanti about her experiences between her death in her former life and her reincarnation into the present one.

In 1961 Dr. Ian Stevenson (1974a, 1974b, 1977, 1978, 1983, 1987) also studied the sources for this case. He writes that “the accounts available to me indicate that Shanti Devi made at least 24 statements of her memories which matched the verified facts.” —By this time the girl should be 25 years old, a women who can have benefits from the myth about her. However it is possible that she just was still deluded about here past.

Dr. K.S.Rawat, interviewed Shanti Devi on February 3, 1986, and October 30, 1987. He had recorded his first interview with Shanti Devi on an audio cassette and the second and third meeting was recorded on a videocassette. – These are just interviews of Shanti Devi cannot be considered as any proof at all.

Shanti Devi narrated everything that happened till her death after childbirth and that included the complicated surgical procedures she underwent.

The researchers were left absolutely stunned by the detailed narration unable to figure out how a little girl like her would even know about such complicated surgical procedures.

Kedar Nath asked Shanti Devi how she became pregnant even when she was unable to get up because of arthritis. To this Shanti Devi explained the entire process of intercourse to Kedar Nath.

Gandhi appointed 15 prominent people including parliamentarians, media members and national leaders for investigating the case. These 15 people took Shanti Devi to Mathura. On the station, she was show a stranger from Mathura and was asked if she could recognize him. She immediately touched his feet and recognized him as her husband’s elder brother, who he actually was. On reaching home, Shanti Devi immediately recognized her father-in-law in the midst of a crowd.

Shanti Devi told that in her past life she had buried some money in a particular location in her house in Mathura. Shanti Devi took the party to the second floor and showed them a spot where they found a flower pot but no money. The girl, however, insisted that the money was there. Kedarnath later confessed that he had taken out the money after Lugdi’s death.

The problem with all these stories is verifying that things occurred exactly as described by credulous witnesses. Far as I can see there isn’t a shred of independently verifiable evidence here. And there is so much room for mistake and falsification in testimonial evidence, especially given the cultural context in which reincarnation was considered true (and in which someone like Gandhi could very much have desired to prove his native religion true), that it doesn’t rise to anywhere close to the ‘extraordinary evidence’ required to confirm an extraordinary claim.

The commission which Gandhi formed said it was real reincarnation case in the report by L. D. Gupta, N. R. Sharma, T. C. Mathur, An Inquiry into the Case of Shanti Devi, International Aryan League, Delhi, 1936.

International Aryan League is The Arya samaj, a hindu sect, that strongly believed in reincarnation, rebirth and other Hindu believes and that was very strict in that. It was against the Musilms and had influence on the Indian National Congress . [Gandhi kind of liked them]

L. D. Gupta was the chairman of Daily Taj newspaper and Gandhi’s friend [Daily Taj was started by Arya Samaj and strongly believed in Hindu philosophy]

N. R. Sharma was leader in the Indian National Congress

T. C. Mathur was a Lawyer [a lot of lawyers happened to be part of the Arya Samaj, but could not get any information about him]

So this investigation was made and published under the influence of a Hindu nationalistic sect, which makes it even less reliable.